Who Was That Black Man?

This Christmas, my dad unwrapped what is likely the coolest gift I’ve ever given him. It was a comic book cover for a superhero idea he…

~This was originally posted on Medium~

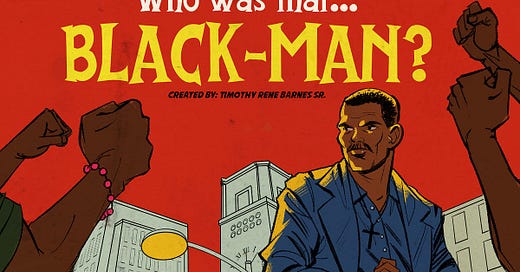

This Christmas, my dad unwrapped what is likely the coolest gift I’ve ever given him. It was a comic book cover for a superhero idea he created and talked about often when I was a kid. The character always seemed like a mix of Blade, Shaft, and my father himself. The heroes name: Black-Man.

What I always loved about his concept is that Black-Man doesn’t need tights or cape. He blends into crowds and often, because of peoples biases, can’t be told apart from other men of his race. This in addition to his swift nature leaves those he saves asking “Who was that black man?”

Black-Man is a bold name and it makes sense coming from a guy like my dad who’s ring tone is James Brown’s “Say It Loud — I’m Black and I’m Proud.” I, on the other hand, keep my phone on vibrate.

With the help of my friend, Joe Karg, we brought my father’s idea to flat, motionless life in this cover:

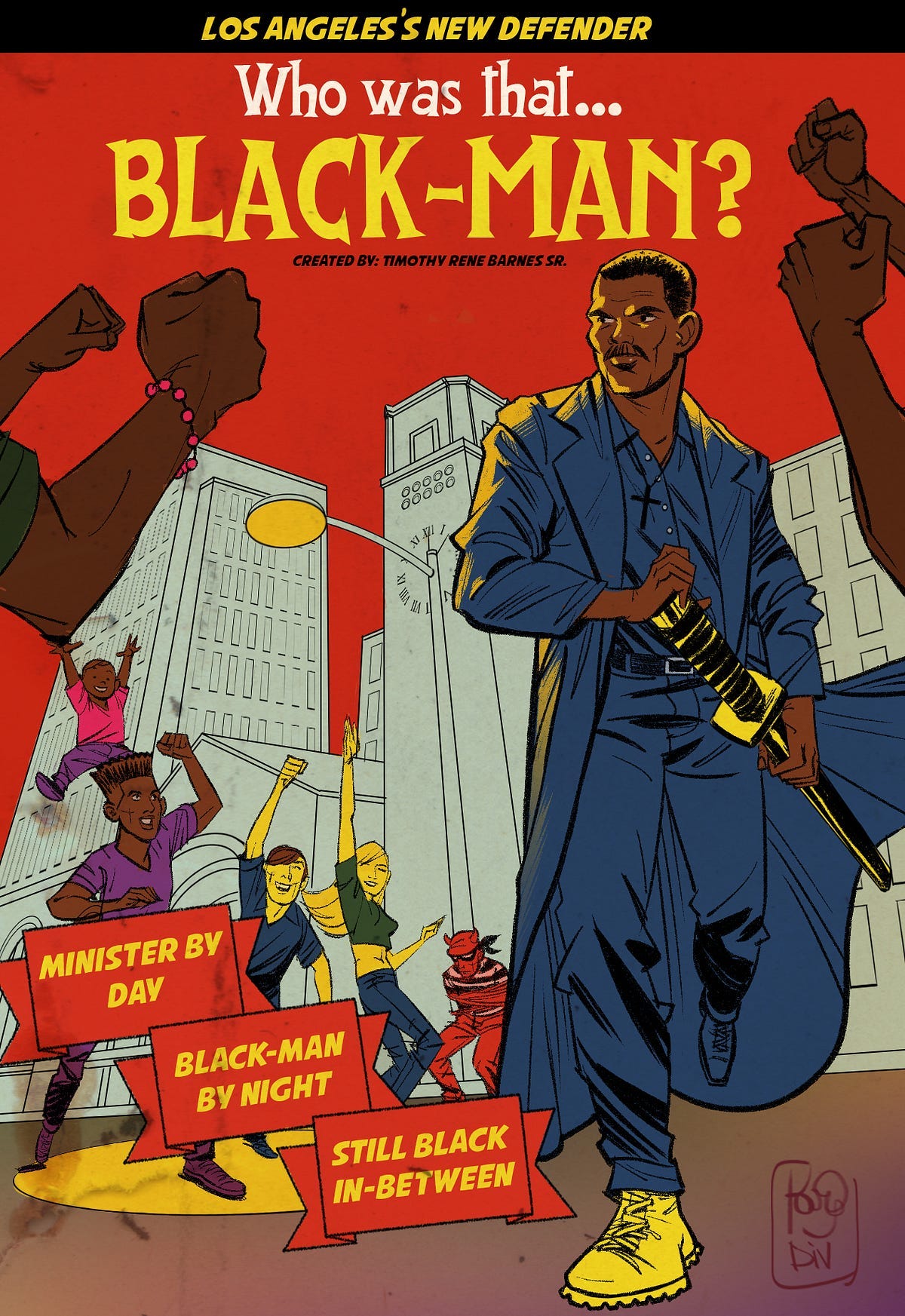

It turns out Leader Comics Group created a hero named Blackman in 1971. I didn’t know this until I made plans to have the cover made just a few weeks ago.

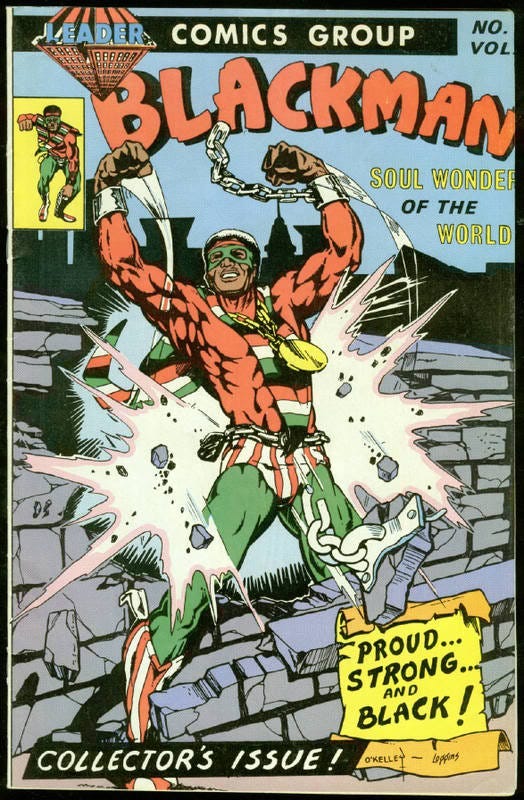

Perhaps my father saw the comic in a shop growing up? It’s hard to find information on Leader Comics or their version of the character, but in the cover for their limited edition first issue, Blackman breaks free of shackles wearing a large gold medallion and is labeled the “Soul Wonder Of The World.” It seems to have tapped into the zeitgeist of “blaxploitation” films; the same reason Marvel developed and released Luke Cage, Hero For Hire in 1972.

Cage is also depicted breaking free of chains on the cover of his debut issue:

Black superheroes and villains created in the 60’s and 70’s include:

Black Lightning

Black Panther

Man-Ape

Black Racer

Black Vulcan

Nubia

Storm

Brother Voodoo

Misty Knight

The Falcon

War Machine

Bumblebee

Blade

Human Top

The original Blackman has a plot that eludes me, but I imagine my dad’s concept for Black-Man is a little different.

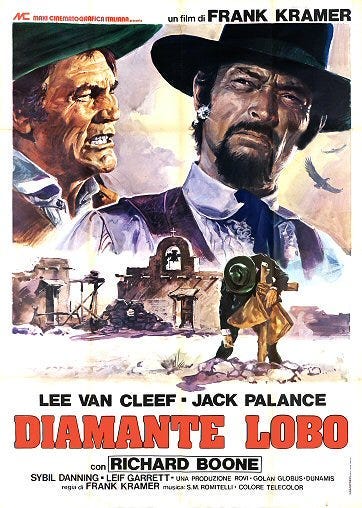

My dad says his character is like The Lone Ranger. In his version, Black-Man wears a long black trench coat with a sword that hangs out from the back. (Blade, anyone!?) He had a twin brother that was a minister who had gotten killed, making him a minister in the day and Black-Man at night. It’s an origin story directly inspired by the poorly reviewed 1976 spaghetti western God’s Gun (Also known as Diamante Lobo, or A Bullet From God.)

Commissioning the cover caused me to consider why black superheroes are so striking on the page and screen. You open up a comic book with a black character on the front page and you’re already tackling preconceived notions of what it’s gonna be about, how good the writing will be, how preachy the tone. When Luke Cage hit Netflix, there was a positive change in my own concept of self. It had a similar result for people I know across the race/gender kaleidoscope. It also perplexed many white people who somehow felt left out. (‘Luke Cage’: Meet the Viewers Who Think It’s Not White Enough)

The unifying factor of campy black heroes like Meteor Man, stoic mythical ones like Storm, and the overtly dark sided ones like Blade is what they reflect upon the world. Most heroes represent the underdog by choice or individual circumstance, but heroes of color are forced by society to represent the underdog regardless of power or strength.

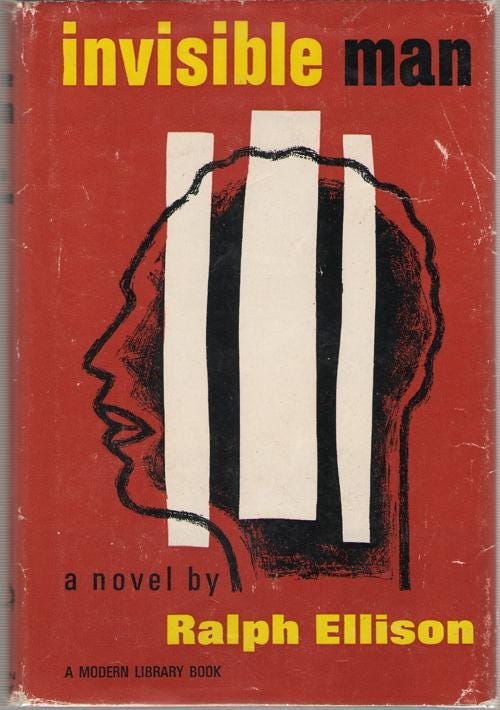

The Black-Man of my fathers mind wasn’t bitten by a spider. Doesn’t even have powers. But he can disappear in a way that is the very essence of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. A true hero with a thousand faces.

“I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves or figments of their imagination, indeed, everything and anything except me.”

― Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man

Does Black-Man practice what he preaches? Does he even believe it? If I were to write this first issue, the question to be answered isn’t who was that black man, but who is he?

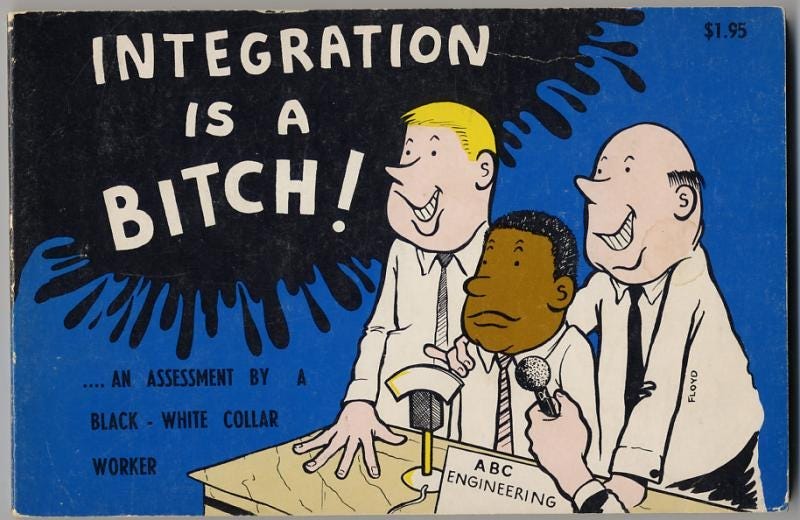

What’s striking to me about the original Blackman comic is that unlike Marvel’s original Luke Cage series written by Archie Goodwin, this medallioned hero was created by an actual black person. His name: Tom Floyd.

There is an incredible lack of information about him, and judging from his book Integration Is A Bitch!, he had a great sense of humor.

Floyd passed away in 2011. I’d love to get more information on all of his work in comics and beyond. If you have any such info, feel free to email me at: timbarnescomedy@gmail.com